“A Life Redeemed: How Brother Chaz X Martin’s Transformation Became a Light for Many”

- Brother Levon X

- 3 hours ago

- 11 min read

BLXCR Editorial Note: We believe these are the stories that matter. When men and women make the decisions toward discipline, service, and purpose—those journeys deserve to be documented, respected, and shared. This interview stands as a living example of how powerful God’s guidance can be when it is applied, not just spoken about. It shows that change is possible, redemption is real, and service to the people is one of the highest forms of faith in action.

A journey from street influence to spiritual purpose—how discipline, faith, and service transformed one man into a servant of the people in Washington, D.C.

In this interview, we sat down with Brother Chaz X Martin to hear, in his own words, what transformation really looks like—when a man who once moved through the world with street influence, pressure, and survival thinking turns himself over to God and becomes committed to saving life instead of wasting it. In Scripture, Christ tells the disciples, “Follow Me, and I will make you fishers of men” (Matthew 4:19). That phrase is deeper than a slogan. It’s a blueprint: when you’ve been taught by a master teacher and brought out of darkness, you don’t keep it to yourself. You go back and reach for others. You become a fisherman—not of fish, but of men.

Brother Chaz’s story begins far from Washington, D.C. He was born in Stuttgart, Germany, where his father served in the military. His mother, a Texas sister, met his father when he was stationed in the States, and out of that union Brother Chaz entered the world. Like many families in America, divorce became part of the story.

His parents split, and after a short time in Maryland, he moved with his mother back to Texas, where he spent most of his childhood. Even as he visited his father about once a month in the DMV, he describes that painful truth a lot of sons understand: a monthly visit is not enough for a young man who needs daily guidance, daily example, and daily protection. His father worked in White House Communications and supported the vice president’s detail—organized, timely, clean, respectful, and strong in presence.

Brother Chaz said it plainly: it wasn’t fear from abuse; it was the natural respect that comes from a father who stands like a father. Even the simple phrase, “I’m going to call your father,” carried weight because a father’s authority—even from a distance—has power when it’s real.

But the gap was still a gap. And in Texas, with his mother working hard, doing her best, and keeping her home as stable as she could—no men running in and out, no chaos being invited through the front door—Brother Chaz still faced the reality that many boys face: a mother cannot be everywhere, and a community can be louder than a household. He explained it in a way that was both honest and painful. A good childhood can still turn into a bad direction when the influence of the enemy is around the clock. It starts innocent—crawfishing in the creek, riding bikes, playing football and basketball.

Then, without warning, it turns into another world: a Black & Mild in the hand, a search for weed, a search for a gun, dealing, fighting, bullying or being bullied, sex too young, and the slow normalization of wickedness. Brother Chaz didn’t romanticize it. He said something that hits like a mirror: if you want to be accepted into a wicked world, you have to be wicked. That’s the trap. That’s the social pressure. And that’s the “manhood” that gets sold to young boys—being aggressive, being disrespectful, collecting women, smoking, drinking, proving something to somebody who doesn’t even love you.

Even in that environment, Allah did not leave him without glimpses of manhood. Brother Chaz named the men who mattered—men who didn’t always lecture him, but whose presence calmed his spirit. He spoke about football coaches who tried, but sometimes didn’t catch the severity until it was late. He remembered Coach Kevin Brooks, who talked to him when his mother brought him over, even though the streets had already started pulling hard. Then he spoke about deeper anchors: his grandfather Hugo—quiet, strong, peaceful, the type of man who didn’t have to ask questions to correct you, because just sitting next to him put the wickedness in submission. He talked about his uncle Michael, who took him fishing, let him ride jet skis, allowed him to bring neighborhood friends, and gave him something many young men are starving for: clean memories with a real man.

He mentioned his stepfather, Michael Carnline, who was easygoing but consistent, never trying to overpower him, never trying to force him, but always present—tolerant, supportive, and respectful. And he remembered a brother named Adrian, who simply took time—picked him up, got him food, bought him toys, let him ride and talk, and showed what responsibility looks like when a man decides a young brother matters. Brother Chaz said a truth that BLXCR stands on: sometimes a man doesn’t have to say a lot to save a young brother. His presence and how he treats him can speak louder than any speech.

When Brother Chaz became old enough to be sent to the DMV area, he began to see the contrast between the two worlds more clearly—Texas influence on one side, structured manhood and military discipline on the other. His father didn’t let the uniform control his personality; he remained a people person, energetic, loving, and honest. But he also demanded truth. Brother Chaz said lying— even small lies—was not tolerated, because trust is the foundation of manhood. Then he shared something that stayed with him: his father cried every time he took him to the airport. Every time.

For years. Not because he didn’t love his son, but because he couldn’t control the distance. That pain matters. A lot of us don’t realize that fathers can hurt too. Brother Chaz didn’t paint his father as a villain. He painted him as a man who loved his son, but circumstances created separation that the streets used as an open door.

Then the story shifts into another blessing: his wife. He met her through a sister he went to school with in Alexandria—Aminata—a friend who later passed away in a car crash. Brother Chaz spoke about that moment with reverence, as if to say some people are placed in your life to produce a specific effect, and once their purpose is fulfilled, Allah calls them home.

Through that connection he met Shawniece, the woman who would become his wife and stand beside him through trials that would have broken most relationships. He described her as quiet, well put together, respectful of herself, raised right, clean, ladylike, and strong. Not the type to throw herself at a man.

She showed loyalty in a way that isn’t common: coming to see him, bringing him food, putting herself at risk to defend him, even when he was wrong. She had a name in the streets—respected by people around him because they saw how she took care of their brother. Before the Nation, she was already playing the role of stability and protection in his life. That’s real. That’s not a fairytale. That’s a Black woman holding the line while a man is still trying to find himself.

And then came the turning point—not gradual, but fast. Brother Chaz said he didn’t grow up knowing the Nation of Islam. He was a hustler who also rapped, a people person who hated seeing others mistreated. World events began to shake his mind: the war in Syria, the loss of life, children dying, suffering abroad while people at home were numb. Then the 2012 earthquake hit closer, and something shifted. He started thinking survival, protection, preparedness.

He bought supplies, ammunition, gear—because in his mind, if the world turns upside down, a man must be able to cover his family. He said something so raw it shows where his mind was: he believed in UFOs more than he believed in God, and he even told his wife that if they came down, he would try to negotiate protection for his family. That’s not to glorify confusion—it’s to show how deep the hunger was for truth, for something bigger, for something that explained what was happening in the world.

Then Allah sent a bridge: a Marine brother named Brother Jarvis, who introduced him to study and to a book that helped connect what he had been feeling to a larger framework. When Brother Chaz read about the Nation of Islam and the reality of what many call “UFOs,” it struck him with force. But more than the science, what grabbed him was the boldness of truth: that a man would declare he was taught by God in person and was sent to seek and save a people who had been rejected and despised—the Black man and woman in North America. Brother Chaz said, in essence: who would say that unless it was real? And that search led him to Muhammad Mosque No. 4.

The way he described it was almost cinematic—pulling up on a Saturday, walking straight to the side door, knocking, and being stopped because it was sisters’ class. But when he said, “I’m trying to join the Nation of Islam,” the brothers erupted with joy—praise to Allah—because they recognized the hunger in a man who is ready. He came back Sunday, late like many of us before training, and even then the energy grabbed him: the order, the discipline, the militancy, the structure, the spirit of the word. He saw the Fruit on post, saw how men carry themselves, saw the seriousness. And he knew: I’m home.

When he went home, the transformation began immediately. The company started to thin out because the conversation changed. When truth enters the room, comfort leaves. People get uncomfortable. Arguments happen. But his wife remained steady. She didn’t speak much against it. She watched the change. Brother Chaz described himself in that early stage as intense—reading constantly, locking himself in the bathroom to study, changing his eating habits, bringing the teachings into the house daily.

He admitted there was an aggressive side that had to be controlled—because when a man first touches knowledge, arrogance can try to rise. He even described a moment with humor and honesty: sitting his wife down, rolling up, and telling her they were going to read Message to the Blackman to each other. He called it being wild—but it also shows the urgency he felt. He didn’t want a separate household. He wanted unity. He wanted his family in the same direction.

The hardest battle wasn’t money. He made it clear: the temptation wasn’t returning to illegal income. The battle was the coping mechanisms—smoking and drinking. And the way he overcame it wasn’t pretending he was perfect. He talked about brotherhood—Brother Oliver checking on him, calling him back when he disappeared, loving him enough to tell him the truth: “We don’t do that.” But also supporting him through the process with patience. That balance—truth with love—kept him from running. And that matters for every person we’re trying to help. Some people don’t need to be thrown away. They need to be held accountable and held up at the same time.

Brother Chaz described the moment the hypocrisy hit him: leaving a call-out, taking his bow tie off in the car, opening the ashtray to grab a leftover, then realizing he had just been telling brothers to clean up. That type of conviction is a mercy. Then an asthma attack followed, and the combination sealed it. His last time smoking was 2014.

For drinking, he even went to bars and told them, “Do not serve me if I come back.” That’s warfare. That’s a man putting fences around his weakness. And he said once Allah cut it off from his mind, the cravings left. That’s not just willpower. That’s help from above.

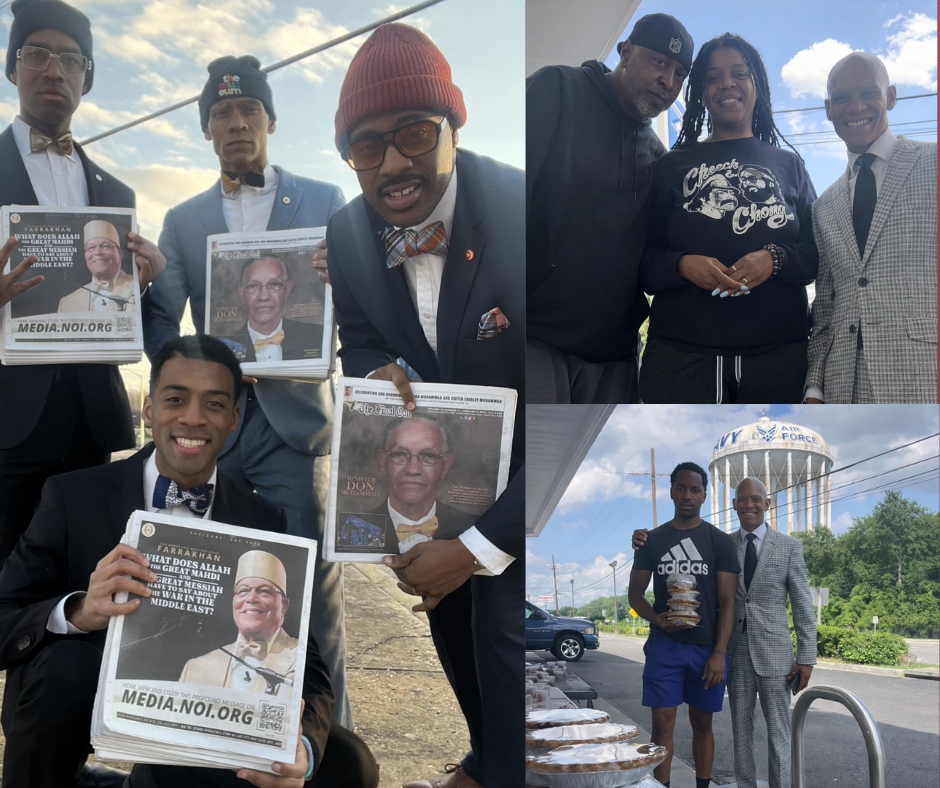

By 10/10/15, the 20th anniversary of the Million Man March, Brother Chaz had already put down those habits. And that day expanded his vision. He saw people from all walks of life, religions, organizations, and backgrounds come to hear the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan. He also saw his own assignment more clearly. He was placed on a Final Call post, had bundles of papers, and Allah blessed him to move them.

That’s where he says he began to discover his purpose: using the Final Call as a tool to reach people, building relationships, speaking to different walks of life, and delivering a universal truth in language people can receive. That day helped shape what Washington, D.C. would later call him: a fisherman.

When we asked about how his family received his transformation, Brother Chaz gave a powerful and honest answer. His father is Caucasian, with Yankee roots from northern Pennsylvania, and military training under the same government the teachings expose. There were arguments—but civilized ones. His father would come with internet narratives, and Brother Chaz would respond with facts. Over time, his father’s respect grew—not only for his son’s discipline, but for the wisdom that helped him navigate raising his other children in a heavily engineered world.

Today, his father supports: donating to Savior’s Day, helping Junior Vanguard with drill, providing suits and shoes for the work, changing his own diet, keeping a Qur’an, and becoming outspoken about the wickedness he once served under. That’s not a small testimony. That’s a household being reshaped.

His mother’s response was more layered, and it was one of the most human parts of the interview. Brother Chaz spoke about colorism, bullying, and the internal struggle many Black people carry from a young age. He made sure to clarify: it wasn’t that she didn’t love Black people—it was the battle of loving herself fully in a world that taught her to question her own beauty. She also carried fear—not of the teachings, but of the danger that comes when Black men stand up and speak boldly, knowing history shows what happens to leaders who challenge a system. But over time, she grew to respect it. She supported. She donated. And she already lived a spirit of service—taking in children, feeding young brothers, being the house where family gathered, braiding hair, holding the community together in quiet ways. She worked with WIC for over twenty years, served Black and Latino families, spoke Spanish fluently, and even in Brother Chaz’s home growing up, the image of Jesus was Black—locks and all. The seed of truth had been around him. The Nation helped bring it into clarity.

By the end of the interview, we understood why people say Brother Chaz is a fisherman. He didn’t claim it as ego.

He credited the training and leadership: Student Regional Minister Khadir Muhammad, Captain Aaron Muhammad, First Officer Frank Muhammad, and the pattern of men who live to reach the people—not talk about it, but do it. Brother Chaz made it plain: he is patterned after men who never stop fishing. He also shared his own formula with humility and seriousness. He is sincere.

He reads people’s temperature. He cannot separate himself from people’s pain. When he sees injustice, harm, children exposed to smoke, brothers under bridges, broken families affecting children—he doesn’t say, “That ain’t me.” He sees it as his responsibility. And he believes his own safety and survival is tied to his service: that Allah covers his household based on the work he does for others. That type of thinking turns outreach into life-or-death mission, not a hobby.

In closing, Brother Chaz offered a message to every young man coming from the streets: Islam is not confined to one culture. It is a way of life that pulls the best out of a man—making him stronger in his home, more disciplined in his mind, more responsible with his family, more useful to his community, and more committed to freedom, justice, and equality.

He explained that the goal isn’t to make a man into “something else,” but to make him into his true self. When a man finds purpose, he no longer needs the same escapes—because he becomes “high” off righteous work. He becomes “drunk” off love for self, love for family, and the joy of building something clean. He learns skills. He produces lawful income. He stops robbing. He stops destroying. He starts creating. He becomes a servant and a humanitarian. He urged readers to listen to the Honorable Minister Louis Farrakhan, read the books of the Honorable Elijah Muhammad, and practice a clean lifestyle—understanding that change may not be overnight, but it is real, and it is possible.

We left this interview with more than notes. We left with a witness. Brother Chaz’s story is not written to entertain. It is written to uplift—especially for brothers who feel trapped, for families trying to hold together, and for any person who believes transformation is out of reach. If Allah can take a man from confusion, habits, street influences, and inner battles—and turn him into a disciplined servant who spends his life inviting others to rise—then there is hope for our people. And if we are fair and honest, we cannot call a mission “hate” when its fruit is men rebuilding families, breaking addictions, serving the community, and calling human beings to live cleaner, think higher, and love harder.

This is the spirit of BLXCR: not gossip, not destruction, not clout. We document the light. We honor the growth. And we tell the kind of story that helps somebody else believe they can change too.

Comments